Palace of the Soviets

| Palace of the Soviets | |

|---|---|

Дворец Советов Dvorec Sovetov | |

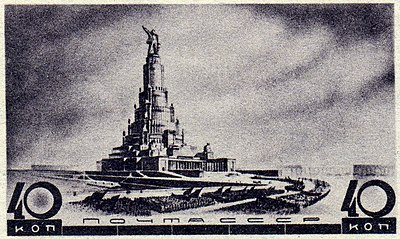

The definitive 1937 design on a postage stamp. Early design specifications required that the Palace should serve as a gigantic triumphal arch for the masses of demonstrants marching through the arena of the grand hall. By 1937 this requirement was dropped. | |

| General information | |

| Status | Never built |

| Type | Administrative and convention center |

| Architectural style | Art Deco, Neoclassicism, Stalinist architecture |

| Location | Moscow, site of the Cathedral of Christ the Saviour |

| Coordinates | 55°44′40″N 37°36′20″E / 55.74444°N 37.60556°E |

| Groundbreaking | 1933[1] |

| Construction stopped | 1941[2][3] |

| Height | 416 m (1,365 ft) (1937 variant)[4][5] |

| Dimensions | |

| Diameter | 130 m (430 ft) (grand hall, internal) 160 m (520 ft) (central core, external)[6][7] |

| Weight | 1.5 million metric tons[8] |

| Technical details | |

| Lifts/elevators | 187[9] |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | Boris Iofan, Vladimir Shchuko and Vladimir Helfreich |

The Palace of the Soviets (Russian: Дворец Советов, Dvorec Sovetov) was a project to construct a political convention center in Moscow on the site of the demolished Cathedral of Christ the Saviour. The main function of the palace was to house sessions of the Supreme Soviet in its 130-metre (430 ft) wide and 100-metre (330 ft) tall grand hall seating over 20,000 people. If built, the 416-metre (1,365 ft) tall palace would have become the world's tallest structure, with an internal volume surpassing the combined volumes of the six tallest American skyscrapers. This was especially important to the Soviet state for propaganda purposes.[10]

Boris Iofan's victory in a series of four architectural competitions held between 1931 and 1933 signaled a sharp turn in Soviet architecture, from radical modernism to the monumental historicism that would come to characterize Stalinist architecture. The definitive design by Iofan, Vladimir Shchuko and Vladimir Helfreich was conceived in 1933–1934 and took its final shape in 1937. The staggered stack of ribbed cylinders crowned with a 100-metre (330 ft) statue of Vladimir Lenin blended Art Deco and Neoclassical influences with contemporary American skyscraper technology.

Work on the site commenced in 1933; the foundation was completed in January 1939. The German invasion in June 1941 ended the project. Engineers and workers were diverted to defense projects or pressed into the army; the installed structural steel was disassembled in 1942 for fortifications and bridges. After World War II, Joseph Stalin lost interest in the palace. Iofan produced several revised, scaled-down designs but failed to reanimate the project. The alternative Palace of the Soviets in Sparrow Hills, which was proposed after Stalin's death, did not proceed beyond the architectural competition stage.

The beginning (1922–31)

[edit]On 30 December 1922 the First All-Union Congress of Soviets announced the creation of the Soviet Union. On the same day Sergei Kirov proposed construction of a new national convention center, which was duly approved by the congress.[11] This, according to the official Soviet narrative, was the beginning of the story of the Palace of the Soviets.[12] Before the congress, in January–May 1919, Petrograd had held an architectural competition for the "Palace of Labor";[13] in October 1922 the Moscow Architectural Society launched a competition for a different "Palace of Labor", endorsed by the same Sergei Kirov.[14] Both projects were large enough to seat any conceivable convention,[a] and none of them could materialize in a country devastated by wars and revolutions.[15][16]

In post-revolution Russian language the word palace (Russian: дворец) denoted a multi-role public building that shared entertainment and administrative functions; as time went by, the administrative side predominated.[15] The word was never applied to residences of political leaders: their private affairs remained a closely guarded secret.[15] During the 1920s, modest "palaces of labor" or "palaces of culture" were actually built.[17] The coveted national palace had to be exceptionally large, impressive and technologically advanced to stand above the crowd.[17] The idea of placing a giant statue of Lenin on top of the national administrative center (originally, the Comintern building) goes back to a 1924 proposal by Viktor Balikhin, then a graduate student at Vkhutemas: "Arc lamps will flood the villages, towns, parks and squares, calling everyone to honor Lenin even at night ...".[18] The proposal was later popularized by Balikhin's rationalist movement, the ASNOVA, but gained little recognition.[19]

The decision to build the "House of Congresses" (Russian: Дом съездов)[20] was made at the end of 1930 or in early 1931, and announced in February 1931.[21] The influences behind the decision cannot be reliably ascertained. Dmitrij Chmelnizki claims Stalin was the project's sole initiator;[21] Sergey Kuznetsov counters that the idea was pitched by Alexei Rykov.[22] The "House of Congresses" was, chronologically, the first of the three megaprojects launched in Moscow in 1931, months before the Moscow Canal and the Moscow Metro.[23] Its initial scope was modest; the architects and the politicians believed that building could be topped out in 1933.[24][25] However, the unchecked ambitions of both groups soon caused a multifold increase in size, scope and cost.[24] In the summer of 1931, the already bloated project was renamed the "Palace of the Soviets".[20]

The architect

[edit]

In February 1931, the government set up a three-tier project management structure. The Construction Council was a decorative[26] political committee chaired by Kliment Voroshilov and later Vyacheslav Molotov;[27][22][28] it served as a proxy for announcing decisions made by Stalin and the Politburo.[26] The subordinate Construction Directorate (USDS) was the actual project management team of Mikhail Kryukov (chair), Boris Iofan (chief architect), Hermann Krasin,[b] Arthur Loleyt and Ivan Mashkov.[21][22] The USDS appointed and supervised the Technical Council, that included dozens of experienced architects, artists and engineers.[27]

Boris Iofan, the second in command in the USDS, immediately assumed the title and role of chief architect.[29][30][31][32] A recent repatriant from Italy and a long-time student of Italian architect Armando Brasini, Iofan was a maverick within the Soviet architectural community and had no obligations to any group.[29][33] He was also a trusted insider of the party elite, with particularly strong ties to Alexei Rykov and Avel Yenukidze.[29] His career with Soviet state clients began in 1922 in Rome[c] and proceeded through the 1920s at an unprecedented and so far unexplained pace.[35] By 1931 he had a proven record of completing high-profile projects, including the enormous[d] House on the Embankment with its cinema hall—the largest modern auditorium in Moscow.[36][22][e] Stalin certainly endorsed Iofan's appointment, probably on Yenukidze's recommendation.[22]

Iofan was difficult to work with soon forcing Kryukov to resign.[37] In the autumn of 1931 the chair of the USDS passed to party apparatchik Vasily Mikhailov, the architect's former superior at the House on the Embankment project.[37] Kryukov, Mikhailov, Rykov, Yenukidze and Iofan's colleagues at the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee would be killed in Stalin's purges, but the unsinkable architect would survive unharmed and retain his office, despite the incriminating connections.[38][f]

Iofan prepared the terms of architectural competitions and controlled all the USDS's paperwork, giving him an advantage over any potential competitor.[31] This obvious conflict of interest provoked speculation that the competitions were rigged in Iofan's favor,[40] or that he was the chosen architect from the very start and the competitions were merely a ruse.[41][42] In the 2010s archival research confirmed this hypothesis, which was afterwards supported by Iofan's biographers Maria Kostyuk, Dmitrij Chmelnizki and Sergey Kuznetsov. As early as 6 February 1931, Iofan devised a three-step, nine-month consultation schedule with a predetermined outcome.[43] The plan was soon implemented in a series of architectural competitions, where Iofan acted as primus inter pares (first among equals) in public and the éminence grise (powerful decision maker) behind the scenes.[43][31] According to Kuznetsov, Iofan initiated and managed the competitions for his own benefit, to harvest free ideas from his unsuspecting colleagues.[41] He never agreed to be a temporary placeholder and did not intend to give up his lead to anyone.[41]

Choice of a site

[edit]In March 1931, the Construction Council chose a compact site in the former Okhotny Ryad Street market, just a few hundred meters (yards) north-west from the Kremlin and Red Square.[20] There were no large or otherwise valuable buildings to raze; demolition of existing low-rise buildings and the relocation of their inhabitants required little time or effort.[20] Left-wing architectural factions immediately disputed this economically sound choice. In April–May the Technical Council reviewed various alternatives and confirmed the selection of the Okhotny Ryad site.[44]

Molotov and Voroshilov thought differently.[45] On 25 May, the Politburo, advised by Molotov and Voroshilov, voted in favor of the Cathedral of Christ the Saviour site.[45] Hannes Meyer and the ASNOVA supported this option. Iofan had secretly studied all the alternatives beforehand and was quite comfortable with the cathedral site.[46] It required extensive demolition and presented so far unknown technical challenges,[47][19] but it was the largest site and it formed a tight visual ensemble with Iofan's House on the Embankment.[46] Most of the Technical Council disagreed. On 30 May, they recommended the sites in Zaryadye or Bolotnaya Square as second-best alternatives; the cathedral site was ranked least acceptable.[48][49][19] Tired of insubordination, Voroshilov invited the stubborn professionals to a meeting with Stalin.[48] On 2 June 1931, Stalin, Molotov, Kaganovich, Voroshilov, Meyer and eight selected architects from the Technical Council convened in the Kremlin, where Stalin presented his arguments in favor of the cathedral site.[45] Kaganovich feared the destruction of an Orthodox shrine would spark an antisemitic backlash and suggested a site in Sparrow Hills, but Stalin's viewpoint prevailed.[5]

Historians disagree over the interpretation of this meeting. According to Kuznetsov, the decision had not yet been finalized, and the architects could still propose other sites.[45] According to Sona Hoisington, the decision was final, but its main objective was not the palace but the destruction of the cathedral,[50] with the project being a purely political statement, made without prior feasibility studies and completely disregarding the economics.[50] According to Chmelnizki, the decision was final; it was the first step in the development of Stalinist architecture.[48] On 5 June 1931, the outcome was sealed by the Politburo.[51] In December the stripped hulk of the cathedral was publicly blown up. The Okhotny Ryad site was also demolished for the construction of the STO Building (1932–1935) and Arkady Mordvinov's residential block on Tverskaya Street (1937–1939).[19]

The idea of destroying cultural heritage was not a novelty to the Soviet regime, as in the period between 1927 and 1940, the number of Orthodox Churches in the Soviet Union fell from 29,584 to less than 500 (1.7%) as a result of demolitions or conversions into secular buildings.[52][page needed]

The four competitions (1931–1933)

[edit]Preliminary round (February–July 1931)

[edit]In April 1931, the chosen architects and architectural groups received terms of the first, preliminary competition. The brief, prepared by Iofan and signed by Kryukov, reiterated the monumentality and emphasizing the uniqueness of the future palace: it should be radically different from any existing public building.[53] It sent a clear message that the entries would be judged not by professionals but by politicians, who do not and would not align with any existing professional faction.[53]

By the end of June, the USDS had collected 15 entries representing all active movements, as well as Iofan and his brother Dmitry.[53] Most, including the Iofans, leaned toward modernist architecture.[54] Iofan had considered various alternatives, and ruled out compact centric floor plans in favor of a sprawling group of buildings aligned along the north–south axis of the cathedral site.[55] The two halls were placed at the ends of the axis, with spacious inner courtyards and a lean, tall tower in between.[56][19] The draft did not impress contemporary observers.[56] The USDS did not name a clear winner but cautiously praised an entry by Heinrich Ludwig,[g] an enormous pentagonal enlargement of Lenin's Mausoleum devoid of any stylistic cues.[58]

International competition (July 1931 – February 1932)

[edit]| Original drafts and modern renderings from the Shchusev Museum of Architecture | |

On 18 July 1931, the USDS announced a public, open, international competition, with entries due by 20 October (later extended to 1 December 1931).[59] In September, the USDS amended the terms and explained the design of the palace would not be awarded to a single architect or a group or firm.[60] The USS claimed no single group could overcome the project's unprecedented challenges; it requires a joint effort of "all living creative forces of the Soviet society".[60] The message foreshadowed the imminent nationalization of the formerly independent professional community, but no one, even the party insiders like Iofan, Alabyan or Shchusev, could predict the outcome.[61] Another covert purpose of the competition—suppression of undesirable architecture in a manner similar to the "Degenerate art" campaign in Germany—would be revealed by Alexey Tolstoy (another party insider) later, just before the announcement of the winners.[62] Tolstoy clearly warned the architects that Gothic architecture, "American skyscraperism" and "corbusianism" had become distinctly unwanted.[63]

The expert jury chaired by Molotov received 112 brief proposals and 160 proper drafts, including 24[h] by foreign architects.[65][66] Dignitaries like Le Corbusier, Walter Gropius or Erich Mendelsohn were preselected and invited by Iofan for a fixed fee.[67][i] Armando Brasini agreed to submit a proposal at no cost.[67] From a professional standpoint the best proposal came from Le Corbusier.[62][j] The Soviet press praised his innovative, logical and convenient floor plan as late as 1940, but the jury felt the high-rise exoskeleton supporting the saddle roof was inappropriate for downtown Moscow.[70]

Most of the sixteen drafts selected by the jury were modernist in inspiration,[20] but the choice of the top three winners surprised and embarrassed everyone involved.[62] The Politburo made the decision secretly, and the Construction Council announced it publicly five days later on 28 February 1931.[51] The three prizes were awarded to Boris Iofan, Ivan Zholtovsky and the virtually unknown British-American autodidact Hector Hamilton.[62][71] Iofan presented a revised version of his earlier proposal, re-aligned along the Moskva River. The draft disposed with former Constructivist novelty[72] The shape of the main hall changed from a parabolic dome to a stack of flat cylinders and, according to Katherine Zubovich, acquired "more italianate form".[71] Le Corbusier despised it as "childish megalomania".[73] Ivan Zholtovsky bizarrely combined Italian Renaissance with the Pharos lighthouse and the Colosseum.[72][71][74] Hamilton's Art Deco draft was uninspiring but the most cohesive of the three.[72] Hamilton, who had never been to Moscow, deliberately avoided any references to both modernist and historical styles.[71] The symmetrical array of staggered rectangular shapes and semicylinders, facing the river, was adorned only with uniform rows of white vertical pylons.[75][62] The "ribbed style" of Hamilton's drafts is strangely reminiscent of almost all Soviet public buildings of the Brezhnev era.[72] It was certainly not unique to Hamilton's entry: similar ribbed facades, a staple of American Art Deco, were also used by Alexey Dushkin, Iosif Langbard, Dmitry Chechulin and Iofan himself.[76]

European left-wing architects could not accept the fact and appealed directly to Stalin.[77] The leaders of the Congrès Internationaux d'Architecture Moderne (CIAM) realized very well that the competition was a matter of politics, rather than art, and that Stalin had the final say.[78] They were willing to cooperate with the dictator and felt betrayed when it turned out he had his own plans.[79] Their message amounted to an ultimatum, threatening to retract all support to the Soviet Union.[80] It is not known if Stalin ever read these letters, but the withdrawal of unwanted "allies" certainly suited him well.[80]

Third and fourth rounds (March 1932 – February 1933)

[edit]

The third, closed, competition among 12 invited teams of architects was held in March–July 1932.[82] In addition to the nine prize-winners of the open competition, at Mikhailov's request the USDS also invited notable constructivists and rationalists.[83] Two future co-authors of the palace, Vladimir Shchuko and Vladimir Helfreich were invited as a reward for their work on the Lenin Library.[84] The USDS required all architects to abandon a sprawling, squat design in favor of a single tall, compact, and monumental structure, avoiding any resemblance to church architecture.[85] The main hall, seating 15,000 people, had to face the Kremlin.[86]

The Ginzburg and Ladovsky teams remained true to modernist ideas.[87] Karo Alabyan and company produced an impressive and novel modernist design—"a ship of state" with three lean "funnels" flanking the river.[87][88] The other architects followed the instructions and presented compact, monumental but uninspiring proposals.[87] Iofan settled for a tall stack of four cylinders, wrapped in rows of white "ribbed style" pylons.[89] The jury declined to appoint a winner and announced yet another round of competition.[89] Stalin, on the contrary, privately notified Kaganovich, Molotov and Voroshilov[m] that "Iofan's plan is unconditionally the best..." and compiled a list of necessary changes.[91][92] Stalin expressly ruled out the alternative designs by Zholtovsky ("...smacks of Noah's ark"), and particularly by Shchusev ("the same cathedral, but without a cross. Possibly, Shchusev hopes to add a cross at a later day").[93]

The fourth and final competition between five selected teams was held in August 1932 – February 1933.[89] This time, all proposals were very similar in composition, although still different stylistically.[94] On 10 May 1933 the Politburo announced the final decision in favor of Iofan.[95][94] The winning design closely followed Iofan's earlier proposal — a compact, ziggurat-like stack of three cylinders perched on a massive stylobate and flanked with colonnades, ramps and grand staircases.[96] Total height of the core structure reached 220 meters (720'),[97] but there was no office tower and no statue of Lenin yet. The proposed statue of the "freed proletarian" was merely 18 meter (60') tall. Structural engineering issues had not been addressed at all.[76] The Politburo was not completely impressed with the result, and instructed Iofan to install a giant statue of Lenin, 50 to 75 meter (160 to 250') tall, on top of the palace.[95] The official narrative published in 1940 presented this proposal as Stalin's personal initiative.[98][94] Molotov hesitated, arguing that the face of Lenin would not be seen from the main plaza, but had to bow to Stalin and Voroshilov.[5]

According to Andrey Barkhin, the true purpose of the fourth stage was to narrow down stylistic choice to one of two alternatives: either following an existing, historical model, or creating something completely new.[74] Iofan managed to suit both sides: although his proposal looked novel, it was in fact a blend of various identifiable prototypes.[74] Iofan himself said the two main inspirations behind his design were the Pergamon Altar and the Victor Emmanuel II Monument which was, in turn, inspired by the Pergamon Altar.[99] The choice was natural for Iofan, because he had often seen the Vittoriano while living in Rome, and because he studied under one of its creators, Manfredo Manfredi.[99] The other identifiable and undisputed design cue is the Art Deco "ribbed style" of exterior walls, which had already been used by other Soviet architects.[74] The dome of the grand hall was inspired by the Centennial Hall in Breslau.[74] Less obvious, speculative sources range from Fritz Lang's Metropolis[74] to Athanasius Kircher's Turris Babel.[100]

Influences and interpretations

[edit]

During the competition period, the state dissolved formerly independent architectural movements and de facto nationalized all architects under the umbrella of state-owned design companies and the Union of Soviet Architects. By the end of 1932, modernist architecture in general, and its constructivist, rationalist and formalist movements in particular, came to a halt, giving way to the emerging Stalinist architecture. Modernist projects laid down earlier were gradually completed and often "improved" to suit the new policy. Architects kept on producing and publishing modernist drafts until at least 1935,[101] but such proposals had no chance to be built.[102] Rudolf Wolters, who came to Novosibirsk in the summer of 1932, reported that by the time of his arrival the provincial party executives had already received orders from Moscow to build "in classical style" only.[103] On the national level, no such orders were formally published; the change appeared to be a natural development within the professional community.[102]

The overwhelming majority of Soviet, Russian and foreign authors, with the notable exception of Antonia Cunliffe, agree the competitions represented a deliberate rejection of modernism in favor of monumental historicism.[104] The connection has always been public but subject to different interpretations. Soviet authors of the 1930s usually appealed to the "improved welfare of the masses".[105] Constructivism was presented as a temporary, low-cost ersatz architecture.[105] Once the nation had overcome the bitter poverty of the 1920s, "the people" (i.e. the communist state) disposed with stopgap solutions and rightfully embraced "quality" architecture.[105] After World War II the "welfare of the masses" fell to an all-time low and Soviet critics adjusted accordingly.[106] They painted modernism as a hostile, subversive influence of the capitalist West that was promptly revealed and suppressed by the party.[106] The reform was effected through the party decrees of the 1930s, starting with the USDS review of the international competition.[107]

In the late 1950s and 1960s modernism became the official style of the Soviet state, and recent history was rewritten again to exonerate the party.[108] Soviet theorists argued that the architects of the 1930s abandoned constructivism voluntarily and then forged the new monumental style on their own.[108] The "excesses" of Stalinist architecture were the architects' fault only.[108] The party, which carefully advised the professionals, bears no responsibility for what was actually built.[108] A toned-down version of the same narrative persisted until the 2000s, notably in the works of Selim Khan-Magomedov.[109] Western authors, likewise, did not produce a plausible explanation until the 2000s publications by Harald Bodenschatz and Christiane Post.[110]

In the late 1990s Dmitry Chmelnizki advanced a different explanation. The competitions were set up by Stalin personally as a complex political provocation.[111] In the opening, self-educational phase, Stalin familiarized himself with all active architectural schools and selected the general direction that would soon become the official style.[111] Then, he artfully degraded the social status and self-esteem of the architectural profession—which was a prerequisite to nationalization.[111] Finally, he destroyed the ties that united the architects into firms, groups and movements. In the end, the former diverse and independent professional community was reduced to a homogenous mass of obedient individuals.[111] Anna Selivanova later published a similar theory.[112]

Opponents like Sergey Kuznetsov argue the existing evidence of Stalin's personal involvement is too scarce to make far-reaching conclusions.[22] There are very few transcripts and quotations reproduced in the Soviet media. The protocols of the Politburo and the journals of Stalin's office in the Kremlin contain very few records related to the palace.[22] Chmelnizki, on the contrary, rates the same Politburo evidence as substantial.[113] Kuznetsov says mundane issues like deliveries of firewood mattered more than architectural follies.[22] Apart from a few publicized meetings, there is no evidence that Stalin ever invited architects to the Kremlin.[22] The only architect who had spoken to Stalin regularly was his personal contractor Miron Merzhanov, who remained modernist throughout the 1930s.[22]

Yet another hypothesis suggested by Sona Hoisington in 2003 views the stylistic change as a direct and unintended consequence of the destruction of the Cathedral of Christ the Saviour.[114] Demolition of the largest building in Moscow left a void in the city fabric that required, at the very least, an equally monumental replacement.[114][49] The modernist drafts received in 1931 could not make up for the loss. They lacked "a center of gravity, a sense of hierarchy", and any connection to the existing city; there was nothing distinctly "Soviet", either.[115] The state demanded "supermonumentality", and found it in Iofan's Art Deco proposal, which was then replicated in lesser projects across the country.[114][49]

The definitive design (1934–1939)

[edit]Forced collaboration

[edit]The decree of 10 May 1933 expressly warned Iofan that the politicians felt free to "help" him by attaching other architects to the design process.[95] The threat materialized on 4 June, when the Politburo co-opted Vladimir Shchuko and Vladimir Helfreich.[116][117] Iofan remained the chief architect, but he now had to deal with two experienced and influential co-authors.[116][n] The theatrical, dramatic visionary architecture that emerged from this collaboration was approved and publicized to great pomp in February 1934 despite a complete lack of technical and economic estimates.[118]

The official narrative presented the outcome as a joint effort of the three peers, but the reality was more complicated.[116] In the second half of 1933, Iofan's team in Moscow and the Shchuko-Helfreich team in Leningrad operated separately.[116] Iofan did not want to alter his 1933 design radically or to increase its already substantial height.[118] Contrary to the instructions received in May, he preferred placing the statue of Lenin on a standalone pedestal or tower, to maintain the balance between the statue and the building.[118] Shchuko and Helfreich thought otherwise, and did not hesitate to perch the giant statue on top of the building, extending its height by 100 metres (330 ft).[119] Initially, their base structure was a slab-sided rectangular block rather than Iofan's stack of cylinders.[119] Iofan objected, but Shchuko appealed directly to the Construction Council.[119] The politicians summoned Iofan and forced him to accept the Shchuko-Helfreich proposal or be removed from the project.[119] He complied, and the design evolved along the middle road between the two extremes.[119]

Placement of a giant statue on top of an already enormous structure caused a disproportional, nonlinear increase in building height. To make the statue visible from the ground, architects had to mount it on a tall but narrow, tapering pedestal—a "skyscraper" standing on the top of the grand hall. The increased height of the pedestal made the statue appear smaller, and the cycle repeated itself. According to the official narrative, experiments with scale models led to the conclusion that the appropriate height of the statue is exactly 100 metres (330 ft).[120] Lenin's head alone had to be almost as large as the Pillar Hall of the House of the Unions.[121] The location of the statue and the design by Sergey Merkurov remained controversial throughout the 1930s and were harshly criticized in public by Boris Korolyov, Nikolai Tomsky, Martiros Saryan and other involved artists.[122]

American experience

[edit]A salient function of the palace project was the transfer of modern technology to the backward Soviet industry.[123] At the end of 1934, Iofan, Shchuko, Helfreikh and their associates departed on a lengthy tour of European and American cities.[124] Their main objectives were the reevaluation of the 1934 design against best American practices, and the research and purchase of modern construction technologies.[125] Moran & Proctor, a leading foundation engineering firm, became the first American company to be hired for the project and would assist the USDS throughout the 1930s.[126] More visits and more contracts, facilitated through the Amtorg network, would follow in subsequent years.[127][128] From a purely architectural perspective, the most important experience was gained at the site of the partially completed Rockefeller Center. Iofan used the stepped-slab motive of 30 Rockefeller Plaza in later projects, and directly inspired careful realignment of the palace's staggered layers.[129][130] These and other subtle exterior changes proceeded throughout the rest of the decade, along with the subsidiary interior design and urban planning tasks, and the creation of factories and workshops.

The definitive exterior design took its final shape by 1937.[131] The number of stacked cylinders was reduced from five to four with progressively decreasing, rather than uniform, spacings between the pylons.[131] The stainless steel moldings attached to the pylons widened progressively with height for a smooth transition from the granite-clad tower to the all-metal statue.[132] The pose and the proportions of the statue also changed.[133] This revised design was presented and discussed at a conference of the Union of Soviet architects in July 1939. A book by Nikolay Atarov describing the design and the construction process in plain language was published one year later.[134]

Size

[edit]The total height of the palace, including the statue, was set at 416 metres (1,365 ft), taller than the recently completed Empire State Building.[4][5][o] Being a much wider structure, the palace was estimated to weigh over 1.5 million tons,[8] and have a gross volume of over 7.5 million cubic meters (9.8 million cu. yd.).[7] Its net internal volume would have surpassed the combined volume of six largest American skyscrapers of the period.[10] The palace would require 350.000 tons of structural steel, six times more than the Empire State Building and almost twice as much as the San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge[10][135]).

The grand hall seating 21 thousand people had to have an inner diameter of 130 metres (430 ft), an outer diameter of 160 metres (520 ft), a height of 100 metres (330 ft) meters and internal volume of 970,000 cubic meters (1.3 million cu. yd.).[6][7] The "small" hall had 5,000 seats and a height of 30 metres (98 ft).[136][p] The "even smaller" Constitution Hall and Reception Hall in the stylobate measured 70 by 36 metres (230 by 118 ft) and 122 by 20 metres (400 by 66 ft).[137] Floors in the office tower were planned to have a usable height of 10 to 12 metres (33 to 39 ft), for even more session halls of various government branches.[138] The exact number of floors was not disclosed.

Enormous as it was, the palace's grand hall was much smaller than Albert Speer's Volkshalle, designed to hold 180 thousand people,[139] but the Russian palace surpassed the Volkshalle in total height.[140]

Structure

[edit]

The completed palace would have consisted of two parts resting on two independent foundations: the circular core with the grand hall, the office tower and the statue of Lenin; and a rectangular stylobate adjacent to the core.[142] The core's concrete foundations rested on limestone bedrock 20 metres (66 ft) below the level of the Moskva River.[142] The much lighter, 90-metre (300 ft) tall stylobate could safely rest on the uppermost limestone sill, 3–5 metres (9.8–16.4 ft) below the ground.[142]

The stylobate design used a traditional steel frame; on the contrary, the frame of the core was radically unconventional.[143] Instead of running the whole vertical height of the building, the palace's load-bearing columns had to wrap around the grand hall.[143] Thus, the frame was split into three distinct segments.[143] The lower segment, 60 metres (200 ft) tall, comprised 32 pairs of vertical columns placed around the grand hall and connected to the foundation slab via massive riveted "shoes".[144] These "shoes" rested on massive steel plates implanted into the concrete slab.[145] Columns of the second segment were placed at a 22° angle, forming a tent over the grand hall up to the 140-metre (460 ft) mark.[146] Above it, a traditional vertical frame would be used.[147] Two massive steel rings, similar to the hoops that hold the staves of a barrel together would hold the tent.[147] These rings, weighing an estimated 28 thousand tons, were the largest, the heaviest and the most expensive elements of the frame.[147] The statue of Lenin, weighing around 6,000 tons, was to be built around its own steel frame, and clad in monel sheeting with an estimated lifetime of two thousand years.[148][q]

External walls followed the American pattern of hollow-body brick infill and granite exterior cladding.[149] According to the official narrative, Stalin instructed the designers to avoid unnecessary visual clutter and use a simple two-tone color scheme.[150] The designers selected greyish blue Ukrainian labradorite for the basement and pale grey granite from the Daut River valley for the rest of the structure.[151]

Engineering systems

[edit]The palace's internal transport infrastructure was designed assuming 50,000 visitors daily.[152] The routes to the grand hall and to the office tower were physically separated; the former relied primarily on stairs and escalators, the latter on elevators.[9] There were to be 130 passenger elevators carrying 25 people each, 27 service elevators and 20 elevators with firefighting equipment.[9] Since no elevator could travel the whole height of the building, visitors to the top floors had to make two or three transfers, sometimes via escalators or stairs.[9]

Electrical consumption of the palace was specified at 90 MW peak, and 90 million kWh per annum.[153] Fault-tolerant, redundant electricity supply required the construction of three new thermal power stations.[153]

Internal cleaning and waste disposal systems contained twelve central vacuum cleaning stations of 750 kW each, and thirty industrial garbage disposal units with a combined capacity of seven tons/day.[154] Heavy air conditioning equipment would have been located below ground level,[155] the conditioned air would be delivered to each seat in the grand hall via a network of ducts running under each row of seats.[156] The placement of air intakes required further research on the distribution of pollutants in the air; the designers knew that the intakes should have been raised to at least 40 metres (130 ft), but the exact height was not yet known.[157] Apparently dust prevention and cleaning the dust were paramount concerns. The designers even provided for vibrating brushes, installed in the floors of the lobbies, for cleaning the soles of the visitors' shoes.[158]

Urban redevelopment

[edit]

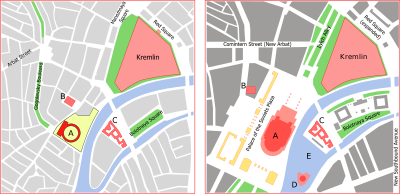

2 by 2 kilometres (1.2 mi × 1.2 mi). Legend: A: Palace of the Soviets (foundation of the core and the northern wing of the stylobate), B: Pushkin Museum (to be relocated), C: House on the Embankment, D: Aviators' Memorial, E: Reflective pool. Note the absence of Lenin's Mausoleum on the plan.

Moscow's planners viewed the palace as the hub of the Ilyich Alley, a new southwest-to-northeast axis aligned along present-day Komsomolsky Prospect, Volkhonka Street, Manezhnaya Square and Sakharov Prospect. The concept developed by the Vesnin brothers and Ivan Leonidov in the 1920s was incorporated in the 1935 urban reconstruction plan in its basic form,[160] and was subsequently reexamined in numerous drafts and proposals.[161] Real construction practice often contradicted the plans: new buildings erected in the center of Moscow often blocked or narrowed the planned avenue.[162]

In 1940, the city approved a revised plan. All buildings between the palace and the Kremlin, including the Moscow Manege, had to be demolished.[160] The Alexander Garden would be leveled into a flat and straight boulevard. The Pushkin Museum building, which partly obstructed the course of the Alley, would be moved north to Gogolevsky Boulevard.[163] Most of it would be absorbed into the palace plaza.[163] The plaza would extend far south-west along the axis of the Alley, and north-west into present-day Arbat District. The Zamoskvorechye island west of the House on the Embankment would disappear, making way for a wide reflective pool.[159] The tip of the island would become a base to the memorial of the Chelyuskin and the projected Pantheon of the Aviators.[159][r]

After World War II, the Ivan Zholtovsky workshop proposed an even larger, and certainly unreal, redevelopment plan for the central squares.[164] Nothing ever came from these fantasies except for the construction of the New Arbat Avenue in the 1960s.[164]

Construction and demolition (1933–1942)

[edit]A geological survey of the site began in 1933[1] and continued into 1934.[165] Drilling to depths of 110 metres (360 ft) confirmed the feasibility of construction.[1] The uppermost limestone sill was too thin to carry the main building's weight,[1] but the second one, 20 metres (66 ft) below the water level, was sufficiently solid.[165] Groundwater in the area contained very little sulfates and chlorides, and was almost always still, thus concrete degradation was not a significant concern.[166]

In the second half of 1934, the builders drilled hundreds of boreholes around the perimeter of the site and pumped hot bitumen into the ground.[167] This formed a watertight vertical curtain extending from the surface to the load-bearing sill, which allowed safe excavation below the river level.[167] Blasting and excavation commenced in January 1935, and continued for more than three years.[168] To clear the pit down to the bedrock, the workers removed 160,000 cubic metres (5,700,000 cu ft) of rock and 620,000 cubic metres (22,000,000 cu ft) of soft soil.[168] The core's concrete foundations, consisting of two concentric rings with an external diameter of 160 metres (520 ft), were completed in January 1938.[169] In a related but independent development, the nearby Dvorets Sovetov ("Palace of the Soviets") metro station, placed just outside the watertight perimeter, was built in less than a year in 1934–1935.[170]

Two types of structural corrosion-resistant alloy steel were developed specifically for the palace: the high-strength DS (ДС) containing copper and chromium, and the regular-strength 3M.[171] The steel beams were rolled, cut and milled at the Verkhnyaya Salda plant, and transported by rail on custom-made flatcars to a transshipment yard in Luzhniki.[172] After inspection and assembly, land tractors and barges hauled the steel to the construction site.[145]

In 1939, when the palace's frame rose above ground level, the propaganda campaign around it reached its peak.[173] The outline of the palace was so omnipresent in Soviet media that, according to Sheila Fitzpatrick, it became more familiar to the average citizen than any existing building.[174] The palace appeared on postcards, stationery and candy wrappers.[175] Filmmakers routinely used special effects to blend the model of the palace into live-action street scenes, as if the structure actually existed.[173]

In the summer of 1940, when the lower load-bearing columns were partially installed, the time to complete the whole frame was estimated at 30 months.[176] A newspaper photograph dated 26 June 1941 attests that by then the frame of the northern wing was largely complete. According to Iofan's biographer Maria Kostyuk, the palace would have certainly been built had it not been for the German invasion.[177]

Immediately after the outbreak of the war, construction was suspended indefinitely;[2][3] many of its 3,600 construction workers were pressed into military service.[178] The USDS factories and workshops were mobilized for the war effort;[3] the stock of structural steel was used for Moscow's anti-tank defenses. Iofan's closest students volunteered for the army and perished in battles.[179] In August–September 1941 project manager Andrey Prokofyev and his engineering staff, along with 560 railcars of the USDS equipment, were evacuated to build the Uralsky Aluminium Plant.[179][180][s] Iofan and Merkurov left Moscow in October under direct orders from Molotov.[178]

At the end of 1941, the remaining workers duly fireproofed and camouflaged the steel frame, and left Moscow for the Urals.[3] In 1942, the frame was disassembled to salvage steel for building railway bridges.[2] With no workers left to maintain the watertight curtain, river water seeped through and eventually flooded the foundations.[182] In 1958–1960 the site was drained and converted into an open-air swimming pool.[183]

After the demolition (1941–1956)

[edit]

Iofan and the remnants of his team spent most of the war in Sverdlovsk working on defense projects.[3] He would later recall that in December 1941, at the peak of the Battle of Moscow, unnamed authorities instructed him to resume work on the palace.[184] However, there is plenty of evidence that he did not have resources to do it.[185] Work on the palace proceeded slowly in Iofan's free time. The next iteration of the design, the so-called Sverdlovsk variant, emerged only at the end of 1943.[185][184] It was superficially similar to the 1937 design, but looked flatter, heavier and lacked the dynamics of the original.[184][186] Iofan removed the ribbed pylons from the upper layers and added many oversized, opulent sculptures.[184] The Sverdlovsk Variant was presented at the Kremlin in 1944 and in 1945, and became the new canon replacing the pre-war designs in mass media.[187]

However, by this time, Stalin had lost interest in the palace.[188][189] Instead, in January 1947, the state concentrated resources on eight lesser skyscrapers in Moscow.[190] Early official announcements presented the new project as a constellation of towers centered around the dominant Palace of the Soviets.[191] Very soon the new towers were given priority over any pre-war plans, and effectively replaced the Palace as the new propaganda icons.[191][192][t] Unfinished projects launched before the war were quietly scrapped or repurposed to the needs of new tenants.[192] By 1953, seven of eight planned towers were actually built, while the palace became a phantom, a fruitless exercise in "paper architecture".[191][192][194]

Of the three titular architects of the palace, Vladimir Shchuko died in 1939, and Vladimir Helfreich moved on to other projects, which included one of the "sisters". Boris Iofan tried to secure the contract for the main building of Moscow State University, but fell out of favor.[195] The university contract, along with all preliminary work by Iofan's team, was awarded to Lev Rudnev.[195] Iofan remained in charge of the unbuilt palace and was instructed to decrease the size and cost.[184] From 1947 to 1956, he presented six new proposals.[184] The 1947–1948 variant decreased to 320 metres (1,050 ft) in height and 5.3 million cubic meters (7 million cu. yd.) in volume.[184] The 1949 variant retained same height, with a further decrease in volume.[184] In 1952–1953, the completion of the "seven sisters" freed up resources and the palace expanded to 411 metres (1,348 ft); in 1953 it decreased again to 353 metres (1,158 ft).[184][u]

On 30 November 1954, Nikita Khrushchev launched a public campaign for the mass construction of affordable housing, and against the "excesses" of Stalinist architecture.[197] Khruschev had no preference for a particular style, but his speechwriters and consultants carefully guided him towards modernist views.[197] The former elders of Stalinist architecture did not dare to object and accepted the new reality. One year later, the "excesses" were condemned in a joint decree of the party and the Soviets,[198] and in 1956 the government dissolved the last refuge of Stalinist art—the Academy of Architecture.[v] The almost forgotten Palace of the Soviets was not mentioned in any of the debates and decrees.[199] Iofan did not want to give up yet. Aided by Helfreich and his new partner Mikhail Minkus, he scaled down the design again to 246 metres (807 ft) in 1954 and to 270 metres (890 ft) in 1956.[199][200]

The other Palace of the Soviets (1956–1962)

[edit]

In the autumn of 1956, Iofan's work finally stopped after the announcement of a new competition for a new Palace of the Soviets.[201] The volume of the new structure was capped at 500,000 cubic meters (700,000 cu. yd.), 15 times less than Iofan's design. The main hall had to seat 4,600 people (five times less), with two lesser halls seating 1,500 people each.[201]

The initial proposal mandated construction on the old site (of the demolished cathedral) which by 1956 was flooded and needed extensive salvage work.[182] In December 1956, the government proposed two alternative locations for the palace, both near Rudnev's University building.[201][202] Proximity to the university tower precluded any high-rise designs; the new palace had to be a sprawling, horizontal, flat structure.[201] However, same proximity suggested that the complete break with Stalinist art had not yet been sealed.[203] The most important government building in Moscow had to be unique; it could not be built cheaply, and it could tolerate at least some "excesses".[203] The neoclassicists believed they were given a chance to redeem Stalinist art in the eyes of Khrushchev.[203] The rising modernists felt Khrushchev's tacit support and saw a chance to impose their own view on the whole Soviet industry.[204]

The first round of the competition was split into two concurrent leagues: the open competition, with 115 entries representing both Stalinists and modernists, and a privately contracted competition with 21 entries.[201] The winning, and probably the most artistically valuable proposal, by Alexander Vlasov, was an outright modernist glass box—a huge winter garden with three oval halls floating in a sea of greenery.[205] Contrary to expectations, Vlasov did not receive a formal prize immediately, but was rewarded later on.[205][206] A similar but less radical design by Leonid Pavlov disposed of the winter garden and added rows of narrow white pylons.[207] The second round of the competition was held in 1959,[208] and attended by Khrushchev himself.[202] This time, all the entries followed the template established by Vlasov and Pavlov, with superficial differences.[208] The new canon of Soviet state architecture, which first took tangible shape in the Soviet pavilion at the Expo 58, was now complete.[208] Vlasov became the head of the new Palace of Soviets construction agency.[209] Very little is known about its work, which ceased after Vlasov's death in 1962.[w][209] The idea behind the Palace of the Soviets was laid to rest.[209] Its intended role was taken over by the Palace of Congresses in the Moscow Kremlin, completed in 1961. The building replaced several heritage buildings, including the old neo-classical building of the State Armoury, and some of the back corpuses of the Great Kremlin Palace. This, and that the architecture of the projected building contrasted with the historic milieu resulted in quite an uproar, particularly after other historic buildings of the Kremlin, such as the Chudov and Ascension cloisters, had already been demolished during the Stalin era, and laws that were introduced by the mid-1950s prohibited the demolition of historic structures, making the construction in some ways illegal.[209][206]

See also

[edit]- Federal Military Memorial Cemetery

- Narkomtiazhprom architectural contest (1934)

- All-Russia Exhibition Centre (1936–1939, 1951–1954)

- Seven Sisters (Moscow) (1947–1954) and the Eighth Sister

- Latvian Academy of Sciences

- Warsaw Palace of Culture and Science

- House of the Free Press in Bucharest

- Symbolism of domes

Notes

[edit]- ^ 8,000 seats in the main hall of the Moscow Palace of Labor, plus various lesser halls

- ^ German (Hermann) Krasin (1871–1947), junior brother of Bolshevik politician Leonid Krasin, was an electrical engineer who designed and built the first electrical distribution network around Moscow. As an urbanist, Krasin developed the public transport policy of Moscow based on a highly centralized hub-and-spokes model.

- ^ The first contract was for the design of the Soviet consulate in Rome. Less known is the fact Iofan and his wife Olga, both members of the Italian Communist Party, were involved in the subversive underground activities of the "Russian Cell" in Rome.[34]

- ^ Ivan Zholtovsky and Alexey Shchusev also had plenty of government contracts. But none of their projects was as large or as conspicuous as the House on the Embankment, which was placed in a "keystone location" across from the Kremlin.[19]

- ^ By February 1931, the residential blocks of the House on the Embankment were almost complete; the first tenants moved in the same month. The cinema was opened in November 1931.

- ^ A list of compromising charges compiled by the NKVD against Iofan also included contacts with Nikolai Bukharin and Karl Radek. Neither Iofan, nor his nominal boss Andrey Prokofyev would ever face prosecution.[39]

- ^ Genrikh (Heinrich) Mavrikievich Ludwig (1893–1973) was a civil engineer with side activities in philosophy, linguistics, occult "sciences" and theories of avant-garde art. The director of the Moscow Architectural Institute since 1928, Ludwig was arrested in 1938. He quickly progressed inside the Gulag system as a construction manager, only to be convicted again, and then obtain yet another managerial job. He survived two decades of imprisonment and eventually returned to teaching at the Stroganov college.[57]

- ^ 11 from the USA, five from Germany, three from France, two from Holland, one each from Estonia, Italy and Switzerland.[64]

- ^ The special status of hired foreigners was not a secret.[68] What was not obvious was the fact that their design contracts precluded further participation in the project.[62]

- ^ In 1933, well after the competition was over, Alexey Shchusev and Grigory Barkhin independently published reviews of the entries. Both authors (successful modernist architects in their own right) admired the Corbusier proposal,[69] although by now the "Corbusianism" was declared undesirable.[63]

- ^ The image is mirrored left-right. The statue was facing the Kremlin, thus the river and the embankment must be on the left, not right.

- ^ The source incorrectly dates it 1931. There is absolutely no evidence that this design, presented in the second half of 1932 and declared the winner in 1933, could have existed in 1931.

- ^ Stalin spent May–August 1931 in Sochi, while Kaganovich, Molotov and Voroshilov took care of business in Moscow. Avel Yenukidze served as a courier for most confidential matters, including the Palace of the Soviets.[90]

- ^ Two other legal co-authors, Georgy Krasin and Sergey Merkurov, were responsible for engineering and sculpture, respectively. They were not involved in architectural design as such.[117]

- ^ The 1961 book lists the height at 420 metres (1,380 ft), probably referring to some revised variant.[7]

- ^ 6000 seats according to the 1961 book.[7]

- ^ Many sources say that the statue was to use stainless steel sheets. The Merkurov report, published in 1939, explains that the available stainless steel was not malleable enough for sculptural work, thus the sculptors specified far more expensive monel.[148]

- ^ In the 1990s, the idea materialized in the monument to Peter I. The 98-meter (320') statue stands on a small man-made island just south of the tip of the historical Zamoskvorechye island.

- ^ Prokofyev retained the core of the USDS throughout the war, hoping to return to the Palace with them one day. During the war, Iofan and Prokofyev worked in the same area (Sverdlovsk and Kamensk-Uralsky) and certainly met each other. In 1947 Prokofyev collaborated with Iofan in his unsuccessful attempts to revive the abandoned project or to secure the University contract.[181]

- ^ Nevertheless, the concept of the Palace as the center of the "constellation" persisted. Chief architect of Moscow Alexander Vlasov kept on promoting the idea as late as September 1952.[193]

- ^ Popular literature often fell behind the changes in the design. For example, in September 1952 Tekhnika Molodezhi still publicized the minimal 320-metre (1,050 ft)-meter version which looks surprisingly compact in comparison to the already built "sisters".[196]

- ^ In 1956, the Academy of Architecture was reorganized into the Academy of Construction and Architecture, with emphasis on technology rather than art. In 1963, the reformed Academy was disbanded altogether. Nothing emerged in its place until the creation of the Academy of Architecture and Construction in 1989.

- ^ Colton wrote in the 1990s that "last word of the project came in mid-1960",[206] but subsequent research has proved that the project continued at a snail's pace into 1962.[209]

Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c d Atarov 1940, p. 72.

- ^ a b c Chmelnizki 2007, p. 286.

- ^ a b c d e Zubovich 2020, p. 55.

- ^ a b Atarov 1940, pp. 17.

- ^ a b c d Colton 1995, p. 260.

- ^ a b Atarov 1940, pp. 109, 110.

- ^ a b c d e Academy of Construction and Architecture 1961, p. 11.

- ^ a b Atarov 1940, p. 70.

- ^ a b c d Atarov 1940, p. 138.

- ^ a b c Colton 1995, p. 332.

- ^ Atarov 1940, p. 23-24.

- ^ Atarov 1940, p. 24.

- ^ Sudzuki 2013, p. 183.

- ^ Sudzuki 2013, p. 191.

- ^ a b c Sudzuki 2013, p. 201.

- ^ Kostyuk 2019, p. 35.

- ^ a b Kostyuk 2019, p. 36.

- ^ Russian: Extract from Balikhin's article, www.artchronica.ru, May 2002 Archived 20 January 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d e f Kostyuk 2019, p. 62.

- ^ a b c d e Hoisington 2003, p. 45.

- ^ a b c Chmelnizki 2007, p. 78.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Kuznetsov 2019, p. 53.

- ^ Colton 1995, pp. 255, 257, 259.

- ^ a b Kuznetsov 2019, p. 55.

- ^ Chmelnizki 2021, p. 47, citing a letter from Molotov to Yenukidze of 5 September 1931..

- ^ a b Chmelnizki 2021, p. 42.

- ^ a b Chmelnizki 2007, pp. 78–79.

- ^ Kostyuk 2019, p. 37.

- ^ a b c Hoisington 2003, p. 57.

- ^ Zubovich 2020, p. 35.

- ^ a b c Kuznetsov 2019, p. 53–54.

- ^ Kostyuk 2019, p. 60.

- ^ Kostyuk 2019, pp. 13, 19, 61.

- ^ Kostyuk 2019, p. 20.

- ^ Kostyuk 2019, pp. 19, 61–62.

- ^ Hoisington 2003, pp. 45–46, 57.

- ^ a b Zubovich 2020, p. 37.

- ^ Kostyuk 2019, p. 19.

- ^ Zubovich 2020, pp. 54–55.

- ^ Hoisington 2003, p. 58.

- ^ a b c Kuznetsov 2019, p. 54.

- ^ Chmelnizki 2021, p. 48: "mockery... served to conceal the work that was going on to construct a new and unified architectural hierarchy.".

- ^ a b Kostyuk 2019, pp. 60–61.

- ^ Chmelnizki 2007, pp. 79–80.

- ^ a b c d Kuznetsov 2019, p. 58.

- ^ a b Kostyuk 2019, p. 63.

- ^ Hoisington 2003, pp. 45–46.

- ^ a b c Chmelnizki 2007, p. 80.

- ^ a b c Hoisington 2003, p. 47.

- ^ a b Hoisington 2003, p. 46.

- ^ a b Chmelnizki 2021, p. 47.

- ^ Dimitry V. Pospielovsky. A History of Soviet Atheism in Theory, and Practice, and the Believer, vol 2: Soviet Antireligious Campaigns and Persecutions, St Martin's Press, New York (1988)

- ^ a b c Chmelnizki 2007, p. 81.

- ^ Chmelnizki 2007, pp. 82–83.

- ^ Kostyuk 2019, pp. 38–39.

- ^ a b Sudzuki 2014, p. 128.

- ^ "Людвиг Генрих Маврикиевич (1893–1973)". Sakharov Center.

- ^ Chmelnizki 2007, p. 83.

- ^ Chmelnizki 2007, p. 84.

- ^ a b Chmelnizki 2007, p. 85.

- ^ Chmelnizki 2007, p. 86.

- ^ a b c d e f Chmelnizki 2007, p. 87.

- ^ a b Chmelnizki 2007, p. 91.

- ^ Kostyuk 2019, p. 42.

- ^ Chmelnizki 2007, pp. 83, 86.

- ^ Kostyuk 2019, pp. 41–42.

- ^ a b Kostyuk 2019, p. 64.

- ^ Union of Soviet Architects 1933, pp. 42, 44, 48.

- ^ Chmelnizki 2007, p. 89.

- ^ Atarov 1940, p. 37.

- ^ a b c d Zubovich 2020, p. 33.

- ^ a b c d Chmelnizki 2007, p. 88.

- ^ Kostyuk 2019, p. 44.

- ^ a b c d e f Barkhin 2016, p. 58.

- ^ Barkhin 2016, pp. 56, 60.

- ^ a b c Barkhin 2016, p. 57.

- ^ Chmelnizki 2007, p. 99.

- ^ Chmelnizki 2007, p. 101.

- ^ Chmelnizki 2007, p. 102.

- ^ a b Chmelnizki 2007, p. 103.

- ^ Hoisington 2003, pp. 56.

- ^ Chmelnizki 2007, p. 113.

- ^ Hoisington 2003, pp. 52–53.

- ^ Hoisington 2003, p. 53.

- ^ Hoisington 2003, p. 51.

- ^ Hoisington 2003, pp. 51–52.

- ^ a b c Chmelnizki 2007, p. 114.

- ^ Hoisington 2003, pp. 54.

- ^ a b c Chmelnizki 2007, p. 115.

- ^ Chmelnizki 2021, p. 50.

- ^ Chmelnizki 2021, p. 51.

- ^ Kuznetsov 2019, p. 54, cites a letter from Stalin to Kaganovich dated 7 July 1932 and published in 2001.

- ^ Chmelnizki 2021, p. 51, cites a letter from Stalin to Kaganovich dated 7 July 1932 and published in 2001.

- ^ a b c Chmelnizki 2007, p. 116.

- ^ a b c "Протокол № 137 заседания Политбюро ЦК ВКП(б) от 10 мая 1933 года (Protocol of the Politburo, 10 May 1933, paragraph 56/43" (in Russian). 10 May 1933. Archived from the original on 30 July 2021. Retrieved 15 June 2021.

- ^ Hoisington 2003, pp. 57–58.

- ^ Hoisington 2003, p. 59.

- ^ Atarov 1940, p. 43.

- ^ a b Hoisington 2003, pp. 58–59.

- ^ Barkhin 2016, p. 59.

- ^ Chmelnizki 2007, p. 133.

- ^ a b Chmelnizki 2007, p. 11.

- ^ Chmelnizki 2007, p. 130, cites Wolters, R. (1933) Spezialist in Sibirien, p. 83.

- ^ Hoisington 2003, pp. 41–42.

- ^ a b c Chmelnizki 2007, p. 13.

- ^ a b Chmelnizki 2007, pp. 13–14.

- ^ Chmelnizki 2007, p. 14.

- ^ a b c d Chmelnizki 2007, p. 16.

- ^ Chmelnizki 2007, pp. 20–21.

- ^ Chmelnizki 2007, p. 25.

- ^ a b c d Chmelnizki 2007, pp. 122–125.

- ^ Kuznetsov 2019, p. 52.

- ^ Chmelnizki 2021, p. 42: "From December 1930 onwards, the subject of the Palace was discussed at the Politburo many times...".

- ^ a b c Kuznetsov 2019, pp. 55–56.

- ^ Hoisington 2003, pp. 48–49.

- ^ a b c d Hoisington 2003, p. 60.

- ^ a b Atarov 1940, p. 45.

- ^ a b c Hoisington 2003, pp. 60–61.

- ^ a b c d e Hoisington 2003, p. 61.

- ^ Atarov 1940, p. 55.

- ^ Atarov 1940, p. 56.

- ^ Academy of Architecture 1939, pp. 40, 43, 70, 77, 78.

- ^ Zubovich 2020, p. 40.

- ^ Zubovich 2020, pp. 40–41, 44.

- ^ Zubovich 2020, p. 44.

- ^ Zubovich 2020, p. 41.

- ^ Zubovich 2020, pp. 42–43.

- ^ Sudzuki 2014, p. 134.

- ^ Barkhin 2016, p. 60.

- ^ Zubovich 2020, p. 53.

- ^ a b Sudzuki 2014, p. 132.

- ^ Atarov 1940, p. 47.

- ^ Sudzuki 2014, pp. 132, 138.

- ^ Atarov 1940, p. 67.

- ^ Atarov 1940, p. 121.

- ^ Atarov 1940, p. 123.

- ^ a b Atarov 1940, p. 109.

- ^ McCloskey, B. (2005). Artists of World War II. Greenwood. p. 63. ISBN 9780313321535.

- ^ Chmelnizki 2007, p. 82 cites memoirs of Albert Speer.

- ^ Atarov 1940, pp. 57, 85.

- ^ a b c d Atarov 1940, p. 77.

- ^ a b c Atarov 1940, pp. 86–87.

- ^ Atarov 1940, pp. 89–90.

- ^ a b Atarov 1940, p. 90.

- ^ Atarov 1940, pp. 90–91.

- ^ a b c Atarov 1940, p. 91.

- ^ a b Academy of Architecture 1939, p. 35.

- ^ Atarov 1940, p. 99.

- ^ Atarov 1940, p. 104.

- ^ Atarov 1940, p. 105.

- ^ Atarov 1940, p. 137.

- ^ a b Atarov 1940, p. 139.

- ^ Atarov 1940, p. 143.

- ^ Atarov 1940, p. 133.

- ^ Atarov 1940, p. 135.

- ^ Atarov 1940, p. 134.

- ^ Atarov 1940, p. 136.

- ^ a b c Tkachenko 2020, p. 51.

- ^ a b Tkachenko 2020, p. 50.

- ^ Tkachenko 2020, p. 85.

- ^ Tkachenko 2020, p. 89.

- ^ a b Tkachenko 2020, pp. 50–51.

- ^ a b Tkachenko 2020, pp. 51–53.

- ^ a b Atarov 1940, p. 73.

- ^ Atarov 1940, p. 80.

- ^ a b Atarov 1940, pp. 73–75.

- ^ a b Atarov 1940, pp. 76–77.

- ^ Atarov 1940, pp. 77–78.

- ^ Kavtaradze, Sergey (2005). "Московскому метро 70 лет" [70 years of Moscow Metro]. World Art Музей (in Russian). 14. ISSN 1726-3050.

- ^ Atarov 1940, p. 69.

- ^ Atarov 1940, pp. 90, 93.

- ^ a b Hoisington 2003, pp. 64–65.

- ^ Hoisington 2003, p. 64 quote Fitzpatrick's 1999 edition of Everyday Stalinism..

- ^ Zubovich 2020, p. 28.

- ^ Atarov 1940, p. 95.

- ^ ""Дворец Советов не был утопией"" [The Palace of the Soviets was not a utopia] (in Russian). gazeta.ru. 19 December 2011.

- ^ a b Zubovich 2020, p. 64.

- ^ a b Kostyuk 2019, p. 52.

- ^ Zubovich 2020, pp. 55, 64, 78.

- ^ Zubovich 2020, pp. 55, 78.

- ^ a b Colton 1995, pp. 365–366.

- ^ Zubovich 2020, p. 107.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Chmelnizki 2007, p. 287.

- ^ a b Zubovich 2020, p. 66.

- ^ Kostyuk 2019, p. 53.

- ^ Kruzhkov, N. (2014). Высотки сталинской Москвы. Наследие эпохи [The high-rise of Stalin's Moscow. Heritage of an epoch] (in Russian). Центрполиграф. ISBN 9785227045423.

- ^ Chmelnizki 2007, p. 260.

- ^ Hoisington 2003, p. 65.

- ^ Chmelnizki 2007, p. 291.

- ^ a b c Chmelnizki 2007, p. 293.

- ^ a b c Colton 1995, p. 329.

- ^ Власов А. В. (Vlasov A.) (1952). "Москва завтра" [Moscow tomorrow]. Техника — молодёжи (5): 5.

- ^ Tkachenko 2020, p. 54.

- ^ a b Chmelnizki 2007, p. 261.

- ^ Трофимов В. (Trofimov V.); Эривански А. (Erivansky A.) (1952). "Восемь вершин" [Eight summits]. Техника — молодёжи (5): 14–15.

- ^ a b Chmelnizki 2007, p. 319.

- ^ Chmelnizki 2007, pp. 328–329.

- ^ a b Chmelnizki 2007, pp. 287, 288.

- ^ Tkachenko 2020, p. 52.

- ^ a b c d e Chmelnizki 2007, p. 335.

- ^ a b Colton 1995, p. 336.

- ^ a b c Chmelnizki 2007, p. 336.

- ^ Chmelnizki 2007, pp. 336–337.

- ^ a b Chmelnizki 2007, p. 340.

- ^ a b c Colton 1995, p. 366.

- ^ Chmelnizki 2007, p. 342.

- ^ a b c Chmelnizki 2007, p. 344-345.

- ^ a b c d e Chmelnizki 2007, p. 345.

References

[edit]Historical sources

[edit]- Union of Soviet Architects (1933). Дворец Советов. Всесоюзный конкурс 1932 г. / Palast der Sowjets. Allunions-Preisbewerbund 1932 (in Russian and German). Всекохудожник.

- Academy of Architecture (1939). Архитектура дворца Советов [Architecture of the Palace of the Soviets]. Издательство Академии Архитектуры СССР. ISBN 9785446072521. (2013 reprint)

- Academy of Construction and Architecture (1961). L. I. Kirillova; G. B. Minervin; G. A. Shemyakin (eds.). Дворец Советов. Материалы конкурса 1957-1959 [Palace of the Soviets. Materials of the 1957-1959 competition] (in Russian). Госстройиздат.

- Atarov, N [in Russian] (1940). Дворец Советов [Palace of Soviets] (in Russian). Московский рабочий. The definitive official description of the final configuration being built in 1940 and the planned mechanical systems.

Modern research

[edit]- Barkhin, A. (2016). "Ребристый стиль высотных зданий и неоархаизм в архитектуре 1920-1930-х" [Ribbed style of high-rise buildings and neoarchaism in the architecture of 1920-1930-s]. Academia. Архитектура и строительство (in Russian) (3): 56–65.

- Chmelnizki, D. (2007). Архитектура Сталина [Stalin's Architecture] (in Russian). Прогресс-Традиция. ISBN 978-5898262716. Note: The 2007 hardcopy Russian edition cites an invalid ISBN-10. Here, the valid code is referenced to the 2013 reprint

- Chmelnizki, D. (2021). Alexey Shchusev. Architect of Stalin's Empire Style. DOM publishers, Berlin. ISBN 9783869224749.

- Colton, T. (1995). Moscow: Governing the Socialist Metropolis. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674587496.

- Hoisington, S. (2003). "Ever Higher: The Evolution of the Project of the Palace of Soviets". Slavic Review. 62 (1). Cambridge University Press: 41–68. doi:10.2307/3090466. JSTOR 3090466. S2CID 164057296.

- Kostyuk, M. (2019). Boris Iofan. Architect behind the Palace of the Soviets. Theory and History, volume 86. Translated by Nicholson, J. DOM publishers, Berlin / Shchusev Museum of Architecture. ISBN 9783869223124.

- Kuznetsov, S. (2019). "Роль Сталина в организации конкурса на проектирование Дворца Советов (1931-1932 гг.)" [The role of Stalin in the organization of the Palace of Soviets competition (1931-1932)] (PDF). Architecture and Modern Information Technologies (in Russian) (3): 51–60.

- Sudzuki, Yu. (2013). "Советские дворцы. Архитектурные конкурсы на крупнейшие общественные здания конца 1910-х – первой половины 1920-х годов как предшественники конкурса на Дворец Советов" [Soviet Palaces. Competitions for the largest public buildings of the late 1910s and first half of the 1920s as the predecessors of the Palace of Soviets competition]. Искусствознание (in Russian): 181–205.

- Sudzuki, Yu. (2014). "Формирование "нового стиля" в процессе окончательного проектирования Дворца Советов" [The formation of the "new style" in the process of final planning of the Palace of Soviets]. Вестник СПБГУ (in Russian) (4): 126–139.

- Tkachenko, S. [in Russian] (2020). "1922–1956 годы. Нереализованные проекты развития центрального композиционного ядра Москвы на примере Аллеи Ильича" [Unrealized Projects of 1922–1956 for the Development of the Central Compositional Core of Moscow on the Example of Ilich Alley]. Academia. Архитектура и строительство (in Russian) (3, 4): 82–91, 50–55.

- Zubovich, Katherine (2020). Moscow Monumental: Soviet Skyscrapers and Urban Life in Stalin's Capital. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691205298.

External links

[edit] Media related to Palace of the Soviets at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Palace of the Soviets at Wikimedia Commons