Josh Gibson

| Josh Gibson | |

|---|---|

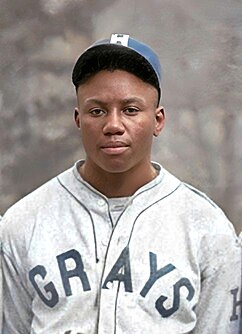

Gibson with the Homestead Grays in 1931 | |

| Catcher | |

| Born: December 21, 1911 Buena Vista, Georgia, U.S. | |

| Died: January 20, 1947 (aged 35) Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, U.S. | |

Batted: Right Threw: Right | |

| Negro leagues debut | |

| July 31, 1930, for the Homestead Grays | |

| Last Negro leagues appearance | |

| 1946, for the Homestead Grays | |

| Negro leagues statistics | |

| Batting average | .372 |

| Hits | 838 |

| Home runs | 174 |

| Runs batted in | 751 |

| Stats at Baseball Reference | |

| Managerial record at Baseball Reference | |

| Teams | |

| Career highlights and awards | |

MLB records

| |

| Member of the National | |

| Induction | 1972 |

| Election method | Negro Leagues Committee |

Joshua Gibson (December 21, 1911 – January 20, 1947) was an American baseball catcher primarily in the Negro leagues. In 1972, he became the second Negro league player to be inducted in the National Baseball Hall of Fame.[1]

Gibson played for the Homestead Grays from 1930 to 1931, moved to the Pittsburgh Crawfords from 1932 to 1936, and returned to the Grays from 1937 to 1939 and 1942 to 1946. In 1937, he played for Ciudad Trujillo in Trujillo's Dominican League and from 1940 to 1941, he played in the Mexican League for Azules de Veracruz. Gibson served as the first manager of the Cangrejeros de Santurce, one of the most historic franchises of the Puerto Rico Baseball League.

Gibson was known as a spectacular power hitter who, by some accounts, hit close to 800 career home runs. (In the Negro League statistical records, his career home run total was 166[2] and MLB.com recognizes 174.)[3] He was known as the "black Babe Ruth";[4] in fact, some fans at the time who saw both Ruth and Gibson play called Ruth "the white Josh Gibson".[5] Gibson never played in the American League or the National League because of the unwritten "gentleman's agreement" that prevented non-white players from participating. He stood 6 ft 1 in (1.85 m) and weighed 210 lb (95 kg) at the peak of his career.[6] He was the first player since Oscar Charleston to win consecutive batting Triple Crowns (leading the league in home runs, runs batted in, batting average) and no batter has achieved the feat since.

On May 28, 2024, Major League Baseball announced that it had integrated Negro league statistics into its records, giving Gibson the highest single-season major league batting average at .466 (1943) and the highest career batting average at .372.[7]

Early life

[edit]

Gibson was born in Buena Vista, Georgia,[8] to Mark and Nancy (née Woodlock) Gibson and had a younger brother, fellow Negro leaguer Jerry, and sister.[9] In 1923, Gibson moved to Pittsburgh, and his father found work at the Carnegie-Illinois Steel Company. Entering sixth grade in Pittsburgh, Gibson prepared to become an electrician, attending Allegheny Pre-Vocational School and Conroy Pre-Vocational School. His first experience playing baseball for an organized team came at age 16 when he played third base for an amateur team sponsored by Gimbels department store where he found work as an elevator operator. Shortly thereafter, he was recruited by the Pittsburgh Crawfords, which in 1928 were still a semi-professional team. The Crawfords, controlled by Gus Greenlee, were the top black semi-professional team in the Pittsburgh area and would advance to fully professional, major Negro league status by 1931.[10]

In 1928, Gibson met Helen Mason, whom he married on March 7, 1929. When not playing baseball, Gibson continued to work at Gimbels after he had given up on his plans to become an electrician to pursue a baseball career.

In the summer of 1930, the 18-year-old Gibson was picked up by the Memphis Red Sox for a game in Scranton, Pennsylvania. Despite going 2 for 4,[11] Red Sox manager Candy Jim Taylor was not impressed by Gibson and said afterward that he would never be a catcher.[12]

He was then recruited by Cumberland Posey, owner of the Homestead Grays, which were the preeminent Negro league team in Pittsburgh; Gibson debuted with the Grays on July 31, 1930. On August 11, Gibson's wife, pregnant with twins, went into premature labor and died while giving birth to a twin son, Josh Gibson Jr., and daughter, Helen, named after her mother. Helen's parents raised the children.[10]

Baseball career

[edit]The Negro leagues generally found it more profitable to schedule relatively few league games and allow the teams to earn extra money through barnstorming against semi-professional and other non-league teams.[13] Thus, it is important to distinguish between records against all competition and records in league games only. For example, against all levels of competition, Gibson hit 69 home runs in 1934; the same year, in 52 league games, he hit 11 home runs.[6][13]

In 1933, he hit .467 with 55 home runs in 137 games against all levels of competition. His lifetime batting average is said to be higher than .350, with other sources putting it as high as .384, the best in Negro league history.[14] In 2021, it was announced by Major League Baseball that the Negro Leagues (1920–1948) would formally be recognized as a major league. Ongoing research by Baseball Reference tabulated that Gibson led his league three times in batting average and once for all major leagues, most notably hitting .417 in 1937. He also led six times in on-base percentage and slugging percentage eight times.[15]

Gibson's Hall of Fame plaque claims he hit "almost 800 home runs in league and independent baseball during his 17-year career."[16] This figure includes both semi-pro competition and exhibition games. According to the Hall's official data, his lifetime batting average was .359.[13] It was reported that he won nine home run titles and four batting championships playing for the Crawfords and the Grays. It is also believed that Gibson hit a home run in a Negro league game at Yankee Stadium that left the stadium. There is no published or film account to support this claim.[17]

Washington Senators owner Clark Griffith once said that Gibson hit more home runs into Griffith Stadium's distant left field bleachers than the entire American League.[18] A 2020 article published by the Society for American Baseball Research provides the supporting details for his homers in major league parks.[19]

Statistics

[edit]The true statistical achievements of Negro league players may be impossible to know as the Negro leagues did not compile complete statistics or game summaries.[13] As of May 28, 2024, Negro league statistics have been integrated into Major League Baseball, and Gibson is now at the top of the leaderboard in many categories.[20][7]

Based on the research of historical accounts performed for the Special Committee on the Negro Leagues, Gibson hit 224 homers in 2,375 at-bats against top black teams, two in 56 at-bats against white major-league pitchers, and 44 in 450 at-bats in the Mexican League.[21] John Holway lists Gibson with the same home run totals and a .351 career average, plus 21-for-56 against white major-league pitchers.[21][page needed] According to Holway, Gibson ranks third all-time in the Negro leagues in average among players with 2,000+ at-bats (trailing Jud Wilson by three points and John Beckwith by one).[21][page needed] Holway lists him as being second to Mule Suttles in homers, though the all-time leader in HR/AB by a considerable margin — with a homer every 10.6 at-bats to one every 13.6 for runner-up Suttles.[21][page needed]

Recent investigations into Negro league statistics, using box scores from newspapers from across the United States, have led to the estimate that, although as many as two-thirds of Negro league team games were played against inferior competition (as traveling exhibition games), Gibson still hit between 150 and 200 home runs in official Negro league games.[13] Though this number appears very conservative next to the claims of "almost 800" home runs. This research also credits Gibson with a rate of one home run every 15.9 at-bats, which compares favorably with the rates of the top nine home run hitters in Major League history. The commonly cited home run totals in excess of 800 are not indicative of his career total in "official" games because the Negro league season was much shorter than the Major League season, typically consisting of fewer than 60 games per year.[22] The additional home runs cited were most likely accomplished in "unofficial" games against local and non-Negro league competition of varying strengths, including the oft-cited "barnstorming" competitions.

In nine of his seasons played in the Negro Leagues, he was selected to the East–West All-Star Game twelve times, which included double duty appearances in 1939 (playing at Comiskey Park and Yankee Stadium), 1942 (Yankee Stadium and Griffith Stadium), and 1946 (Griffith and Comiskey).

Death

[edit]In early 1943, Gibson fell into a coma and was diagnosed with a brain tumor. After regaining consciousness, he refused the option of surgical removal and lived the next four years with recurring headaches. In 1944, Gibson was hospitalized in Washington, D.C., at Gallinger Hospital for mental observation.[23] On January 20, 1947, Gibson died of a stroke at 35 years old in Pittsburgh. He was buried at the Allegheny Cemetery in the Lawrenceville neighborhood of Pittsburgh, where he lay in an unmarked grave until a small plaque was placed in 1975.[24]

Legacy

[edit]

Larry Doby, who broke the American League color barrier in July, felt that Gibson was the best black player in 1945[25] and 1946;[26] over even Jackie Robinson, who became the first black player in modern Major League history in April 1947 playing in the National League. Doby said in an interview later, "One of the things that was disappointing and disheartening to a lot of the black players at the time was that Jack was not the best player. The best was Josh Gibson. I think that's one of the reasons why Josh died so early — he was heartbroken."[26]

In 1972, Gibson and Buck Leonard became the second and third players, behind Satchel Paige, inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame based on their careers in the Negro leagues.[27] Gibson's Hall of Fame plaque claims "almost 800" home runs for his career, although this number cannot be substantiated.

Although validation of statistics continues to prove difficult for Negro league players, the lack of verifiable figures has led to various amusing tall tales about players such as Gibson.[28] An example of such: in the bottom of the ninth at Pittsburgh, down a run, with a runner on base and two outs, Gibson hits one high and deep, so far into the twilight sky that it disappears, apparently winning the game. The next day, the same two teams are playing again, now in Washington. Just as the teams have positioned themselves on the field, a ball falls out of the sky, and a Washington outfielder grabs it. The umpire yells to Gibson, "You're out! In Pittsburgh, yesterday!"[29]

The U.S. Postal Service issued a 33-cent U.S. commemorative postage stamp which features a painting of Gibson and includes his name.[30]

In 2000, he ranked 18th on The Sporting News' list of the 100 Greatest Baseball Players, the highest-ranking of five players to have played all or most of their careers in the Negro leagues. (The others were Satchel Paige, Buck Leonard, Cool Papa Bell and Oscar Charleston.) He was nominated as a finalist for the Major League Baseball All-Century Team in the same year.

At PNC Park, home of Pittsburgh's Major League Baseball (MLB) franchise, the Pittsburgh Pirates, an exhibit honoring the city's two Negro league baseball teams was introduced in 2006. Located by the stadium's left field entrance and named Legacy Square, the display featured statues of seven players who competed for the Homestead Grays and Pittsburgh Crawfords, including Gibson.[31] In 2015, without any public announcement, the Pirates removed all seven statues from the Legacy Square area. Ultimately, they were donated to the Josh Gibson Foundation and sold at auction to benefit the Foundation.[32][33] Most of the statues that were originally located at Legacy Square in PNC Park, including Gibson's, are now displayed at the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City, Missouri.[34]

In 2009, a statue of Gibson was installed inside the center field gate of Nationals Park along with ones of Frank Howard and Walter Johnson.

He was named to the Washington Nationals Ring of Honor for his "significant contribution to the game of baseball in Washington, D.C." as part of the Homestead Grays on August 10, 2010.

Ammon Field in Pittsburgh was renamed Josh Gibson Field in his honor and is the site of a Pennsylvania State Historical Marker.[35]

His son, Josh Gibson, Jr., played baseball for the Homestead Grays.[36] His son also was instrumental in the forming of the Josh Gibson Foundation.[37][38][39]

An opera based on Josh Gibson's life, The Summer King, by composer Daniel Sonenberg, premiered on April 29, 2017, in Pittsburgh.[40][41]

In popular culture

[edit]

- In 1996, Gibson was played by Mykelti Williamson in the made-for-cable film Soul of the Game, which also starred Delroy Lindo as Satchel Paige, Blair Underwood as Jackie Robinson, Edward Herrmann as Branch Rickey, and Jerry Hardin as Commissioner Happy Chandler.

- The character of Leon Carter, played by James Earl Jones in the 1976 film The Bingo Long Traveling All-Stars & Motor Kings, is based on Gibson.

- The character Josh Exley, played by Jesse L. Martin in the 1999 The X-Files episode "The Unnatural", is based on Gibson.

Miscellaneous

[edit]- Gibson played baseball in the United States, Cuba, Puerto Rico, Dominican Republic, and Mexico, with a lifetime batting average of .354–.384, depending on which statistics are counted.[42]

- Starting in 1932–1933, Gibson played in Puerto Rico. In 1941–1942, Gibson played for the Puerto Rican Professional Baseball League. Playing for the Cangrejeros de Santurce, Gibson won the batting title that season with an average of .480, recognized as the record for that league.[43][44]

- Barry Bonds referred to "Josh Gibson's 800 home runs" in his post-game press conference after hitting his 756th MLB home run.[45]

- Gibson was said by Buck O'Neil to have created a particular sound like dynamite when he hit the ball that he had heard only three times during his lifetime in baseball. Babe Ruth was the first, when O'Neil was young, Gibson was the second, when his Homestead Grays came to play O'Neil's Kansas City Monarchs, and Bo Jackson was the third, 50 years later, when Jackson was called up by the Kansas City Royals and O'Neil was a scout for the Chicago Cubs.[46][47][48]

Career statistics

[edit]Negro leagues

[edit]According to the Macmillan Baseball Encyclopedia, Josh Gibson's Negro official league stats were as follows: Total years played: 16. Total games played: 501. Total career at bats: 1679. Total career hits: 607. Total career 2B hits: 89. Total career 3B hits: 35. Total career HR: 146. Total career SB: 11. Career batting average: .362.

The first official statistics for the Negro leagues were compiled as part of a statistical study sponsored by the National Baseball Hall of Fame and supervised by Larry Lester and Dick Clark, in which a research team collected statistics from thousands of boxscores of league-sanctioned games.[13] The first results from this study were the statistics for Negro league Hall of Famers elected prior to 2006, which were published in Shades of Glory by Lawrence D. Hogan. These statistics include the official Negro league statistics for Josh Gibson:[13]

| Year | Team | G | AB | R | H | 2B | 3B | HR | RBI | SB | BB | BA | SLG |

| 1930 | Homestead | 21 | 71 | 13 | 24 | 2 | 0 | 5 | 17 | 0 | 5 | .338 | .577 |

| 1931 | Homestead | 32 | 124 | 26 | 38 | 8 | 5 | 6 | 23 | 0 | 11 | .306 | .597 |

| 1932 | Pittsburgh | 49 | 191 | 34 | 62 | 10 | 5 | 8 | 28 | 0 | 21 | .325 | .555 |

| 1933 | Pittsburgh | 38 | 138 | 32 | 54 | 6 | 2 | 8 | 31 | 1 | 9 | .391 | .638 |

| 1934 | Homestead | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | .500 | .500 |

| 1934 | Pittsburgh | 52 | 190 | 39 | 62 | 14 | 3 | 11 | 27 | 2 | 19 | .326 | .605 |

| 1935 | Pittsburgh | 35 | 145 | 37 | 54 | 10 | 2 | 8 | 29 | 7 | 16 | .372 | .634 |

| 1936 | Pittsburgh | 26 | 90 | 27 | 39 | 3 | 2 | 6 | 18 | 1 | 13 | .433 | .711 |

| 1937 | Homestead | 25 | 97 | 39 | 41 | 7 | 4 | 13 | 36 | 1 | 17 | .423 | .979 |

| 1938 | Homestead | 28 | 105 | 31 | 38 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 9 | 1 | 13 | .362 | .505 |

| 1939 | Homestead | 21 | 74 | 22 | 27 | 3 | 2 | 10 | 22 | 3 | 20 | .365 | .865 |

| 1940 | Homestead | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | .000 | .000 |

| 1942 | Homestead | 42 | 138 | 36 | 42 | 6 | 1 | 7 | 38 | 2 | 32 | .304 | .514 |

| 1943 | Homestead | 55 | 192 | 69 | 91 | 24 | 5 | 12 | 74 | 3 | 39 | .474 | .839 |

| 1944 | Homestead | 34 | 123 | 27 | 44 | 4 | 3 | 9 | 34 | 1 | 15 | .358 | .659 |

| 1945 | Homestead | 17 | 62 | 12 | 17 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 15 | 0 | 11 | .274 | .532 |

| 1946 | Homestead | 33 | 111 | 22 | 32 | 6 | 2 | 7 | 31 | 0 | 12 | .288 | .568 |

| Total | 16 seasons | 510 | 1855 | 467 | 666 | 109 | 41 | 115 | 432 | 22 | 255 | .359 | .648 |

Dominican League

[edit]| Year | Team | AB | H | BA |

| 1937 | Ciudad Trujillo | 53 | 24 | .453 |

Source:[21][page needed]

Mexican League

[edit]| Year | Team | G | AB | R | H | 2B | 3B | HR | RBI | SB | BB | BA | SLG |

| 1940 | Veracruz | 22 | 92 | 32 | 43 | 7 | 4 | 11 | 38 | 3 | 16 | .467 | .989 |

| 1941 | Veracruz | 94 | 358 | 100 | 134 | 31 | 3 | 33 | 124 | 7 | 75 | .374 | .754 |

| Total | 2 seasons | 116 | 450 | 132 | 177 | 38 | 7 | 44 | 162 | 10 | 91 | .393 | .802 |

Source:[49]

Cuban (Winter) League

[edit]| Year | Team | AB | R | H | 2B | 3B | HR | RBI | SB | BA | SLG |

| 1937/38 | Habana | 61 | 11 | 21 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 13 | — | .344 | .607 |

| 1938/39 | Santa Clara | 163 | 50 | 58 | 7 | 3 | 11 | 39 | 2 | .356 | .638 |

| Total | 2 seasons | 224 | 61 | 79 | 10 | 5 | 14 | 52 | — | .353 | .629 |

Source:[50]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ National Baseball Hall of Fame, Josh Gibson "Gibson, Josh | Baseball Hall of Fame". Retrieved April 16, 2015

- ^ "Josh Gibson Stats, Height, Weight, Position, Rookie Status & More".

- ^ Treisman, Rachel (May 29, 2024). "The Negro Leagues are officially part of MLB history—with the records to prove it and most career". Sports. NPR. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Josh Gibson". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. January 16, 2024.

- ^ Brashler, William (1978) Josh Gibson: A Life in the Negro Leagues. Chicago: Ivan R. Dee. ISBN 1-56663-295-1

- ^ a b Riley, James A. (1994). The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues. New York: Carroll & Graf. ISBN 0-7867-0959-6.

- ^ a b Kepner, Tyler. "As MLB changes its records, Josh Gibson replaces Ty Cobb as all-time batting leader". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ Hellmann, Paul T. (May 13, 2013). Historical Gazetteer of the United States. Routledge. p. 221. ISBN 978-1135948597. Retrieved November 30, 2013.

- ^ Brashler, William (1978). Josh Gibson- A life in the Negro Leagues. New York, N.Y.: Harper& Row. p. 5. ISBN 0-06-010446-5.

- ^ a b Ribowsky, Mark (2004). Josh Gibson: The Power and the Darkness. Urbana, Illinois, USA: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-07224-3.

- ^ "1930 Memphis Red Sox - Seamheads Negro Leagues Database". www.seamheads.com. Retrieved October 21, 2021.

- ^ "Jim Taylor – Society for American Baseball Research". Retrieved October 21, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g Hogan, Lawrence D. (2006). Shades of Glory: The Negro Leagues and the Story of African-American Baseball. Washington, D.C.: National Geographic. ISBN 0-7922-5306-X.

- ^ Kroichick, Ron (August 27, 2010). "NEGRO LEAGUE LEGEND / THE BLACK BABE / Josh Gibson may have been the greatest home-run hitter ever". The San Francisco Chronicle.

- ^ "The Negro Leagues Are Major Leagues | Baseball-Reference.com".

- ^ "Gibson, Josh". Baseball Hall of Fame. Retrieved March 19, 2013.

- ^ Neyer, Rob (May 19, 2008). "Did Gibson hit one out of Yankee Stadium?". ESPN.com. Retrieved June 3, 2024.

- ^ Lowry, Philip (2006). Green Cathedrals. Walker & Company. p. 236. ISBN 978-0-8027-1608-8.

- ^ sabr. "Josh Gibson Blazes a Trail: Homering in Big League Ballparks, 1930–1946 – Society for American Baseball Research". Retrieved June 12, 2022.

- ^ https://www.cbssports.com/mlb/news/mlb-finally-integrates-negro-leagues-statistics-into-historical-records-where-does-josh-gibsons-name-land/

- ^ a b c d e Holway, John B. (2001). The Complete Book of Baseball's Negro Leagues: The Other Half of Baseball History. Fern Park, Florida: Hastings House Publishers. ISBN 0-8038-2007-0.[page needed]

- ^ 1939 in baseball#Negro National League final standings

- ^ "Negro League Star Held in Hospital for Mental Observation". Ghosts of DC. August 7, 2012. Retrieved August 14, 2012.

- ^ "Josh Gibson A Life that Inspired a Movie Character". BingoHall Blog. Archived from the original on December 8, 2014. Retrieved December 5, 2014.

- ^ "800 Home Run Club, Josh Gibson: The African-American Babe Ruth by Liz Banks, 31 December 2013".

- ^ a b Moore, Joseph Thomas (1988). Pride and Prejudice: The Biography of Larry Doby. New York: Praeger Publishers. p. 30. ISBN 0275929841.

- ^ "Buck Leonard and Josh Gibson are elected to the Hall of Fame". Baseball Hall of Fame. Retrieved June 12, 2022.

- ^ Peterson, Robert (1970). "Only the Ball Was White".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Negro Leagues Baseball eMuseum: Personal Profiles: Josh Gibson". nlbemuseum.com. Retrieved August 11, 2022.

- ^ The following article includes a photo of a poster-size copy of the postage stamp. "Awards To Honor Legacy Of Negro League Baseball Great". CBS Pittsburgh KDKA-2. CBS Local Media. August 12, 2011. Retrieved October 21, 2011.

- ^ Finder, Chuck (June 27, 2006). "Pirates Put History on Display". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved June 27, 2014.

- ^ "Is there no place in Pittsburgh for Negro League all-stars?". Andscape. November 2016. Retrieved August 24, 2019.

- ^ O’Neill, Brian (July 30, 2015). "Statues honoring Negro Leagues gone from PNC Park entrance". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved August 24, 2019.

- ^ "US and Canadian Baseball Statue Database". Offbeat.Group.Shef.AC.UK. Retrieved August 24, 2019.

- ^ "Joshua (Josh) Gibson Marker". Hmdb.org. Retrieved March 19, 2013.

- ^ "Negro Leagues Baseball eMuseum: Personal Profiles: Josh Gibson, Jr". Coe.ksu.edu. August 11, 1930. Archived from the original on July 23, 2011. Retrieved August 8, 2011.

- ^ "Josh Gibson Foundation". Joshgibson.org. Retrieved August 8, 2011.

- ^ Maroon, Annie (June 25, 2011). "Pittsburgh's Negro League heritage celebrated". Pittsburgh Tribune-Review. The Batchelor Pad blog. Archived from the original on July 23, 2014. Retrieved October 21, 2011.

The Josh Gibson Foundation ... will host the Josh Gibson Centennial Negro League Gala on Aug. 13 at the Wyndham Grand Pittsburgh. The event will honor the 100th anniversary of the Homestead Grays and Pittsburgh Crawfords slugger's birth in 1911.

- ^ Gonzalez, Alden (February 1, 2010). "Negro Leagues Museum in financial straits: Deficit reflects dwindling donations in struggling economy". Kansas City Royals website. MLB Advanced Media. Archived from the original on December 6, 2014. Retrieved October 21, 2011.

... Sean Gibson, the great-grandson of Hall of Famer Josh Gibson and the head of the Josh Gibson Foundation in Pittsburgh.

- ^ Keyes, Bob (April 30, 2017). "Portland composer fulfills dream, hits home run with baseball opera". Portland (Me.) Press Herald (PressHerald.com). Portland Press Herald. Retrieved May 4, 2017.

- ^ O'Neill, Brian (May 4, 2017). "Josh Gibson's epic story takes center stage". Pittsburgh Post Gazette. Retrieved May 4, 2017.

- ^ "ESPN.com: No joshing about Gibson's talents". Espn.go.com. Retrieved August 8, 2011.

- ^ "Vázquez, Edwin; Beisbol De Ligas Negras-James "Cool Papa" Bell Beisbox Caribe; December 22, 2006". Archived from the original on August 16, 2006. Retrieved October 13, 2007.

- ^ "Bjarkman, Peter C.; "Winter pro baseball's proudest heritage passes into oblivion"". Archived from the original on November 7, 2007. Retrieved October 13, 2007.

- ^ Curry, Jack (August 9, 2007). "No. 757 for Bonds follows long night". The New York Times.

- ^ Buck O’Neil with Steve Wulf & David Conrads (1996). I was Right on Time. New York: Simon & Schuster. pp. 3–4.

- ^ "Buck O'Neil | Society for American Baseball Research". sabr.org. Retrieved October 7, 2019.

- ^ The Ultimate Ball Field Sound, March 8, 2013, archived from the original on December 12, 2021, retrieved October 7, 2019

- ^ Treto Cisneros, Pedro (2002). The Mexican League: Comprehensive Player Statistics, 1937–2001. Jefferson, North Carolina, USA: McFarland & Company. p. 151. ISBN 0-7864-1378-6.

- ^ Figueredo, Jorge S. (2003). Cuban Baseball: A Statistical History, 1878–1961. Jefferson, North Carolina, USA: McFarland & Company. pp. 222, 225. ISBN 0-7864-1250-X.

Further reading

[edit]Articles

[edit]- "Josh Gibson Makes 'Time' Magazine". Cleveland Call-Post. July 24, 1943. p. 10-A.

- "Gibson's Long Homer Features Grays' Victory". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. May 23, 1946. p. 15.

- Young, A. S. "Doc". "Inside Sports: Jimmy Crutchfield Remembers Josh". Jet. April 7, 1955. p. 55.

- Peterson, Robert. "Greatest Battery Ever". Boys' Life. April 1971. p. 32–33, 52–53

- "Josh Gibson: Greatest Slugger of 'em All". Ebony. May 1972. pp. 45–46, 48–49.

- "Letters (cont.): Josh Gibson". Ebony. July 1972. p. 17.

- "Josh Gibson, the 'Black Babe Ruth,' Honored With Historical Marker". Jet. October 21, 1996. p. 55.

- Janik, James. "Legendary Power". Boys' Life. August 2001. p. 42–43.

Books

[edit]- Brashler, William. Josh Gibson: a Life in the Negro Leagues. Harper & Row, 1978.

- Buckley, James Jr. 1,001 Facts About Hitters. DK Publishing, 2004.

- Figueredo, Jorge. Cuban Baseball: A Statistical History. McFarland & Company, 2003.

- Holway, John. The Complete Book of Baseball's Negro Leagues. Hastings House, 2001.

- Lester, Larry. Black Baseball's National Showcase. University of Nebraska Press, 2001.

- Peterson, Robert. Only the Ball Was White. Gramercy, 1970.

- Ribowsky, Mark. Josh Gibson The Power and The Darkness. University of Illinois Press, 2004.

- Riley, James. The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues. Carrol & Graf, 1994.

- Rogosin, Donn. Invisible Men. Atheneum, 1983.

- Snyder, Brad. Beyond the Shadow of the Senators. McGraw-Hill, 2004.

- Treto Cisneros, Pedro. The Mexican League: Comprehensive Player Statistics. McFarland & Company, 2002.

External links

[edit]- Josh Gibson at the Baseball Hall of Fame

- Career statistics from MLB, or Baseball Reference, or Baseball Reference (Minors) or Seamheads

- Josh Gibson page at Pace University

- Georgia Sports Hall of Fame

- News article on 2004 compilation of Negro League statistics – Includes home run to at-bat ratio comparison.

- ESPN Sportcentury article on Josh Gibson

- An opera about Josh Gibson in The Wall Street Journal

- Josh Gibson at Find a Grave

- 1911 births

- 1947 deaths

- African-American baseball players

- American expatriate baseball players in Mexico

- Azules de Veracruz players

- Baseball players from Georgia (U.S. state)

- Burials at Allegheny Cemetery

- Habana players

- History of Pittsburgh

- Homestead Grays players

- Mexican Baseball Hall of Fame inductees

- Leopardos de Santa Clara players

- National Baseball Hall of Fame inductees

- Negro league hitting Triple Crown winners

- Neurological disease deaths in Pennsylvania

- People from Buena Vista, Georgia

- Pittsburgh Crawfords players

- Baseball players from Pittsburgh

- American expatriate baseball players in Cuba

- Memphis Red Sox players

- 20th-century American sportsmen